E book Evaluate

Vera, or Religion

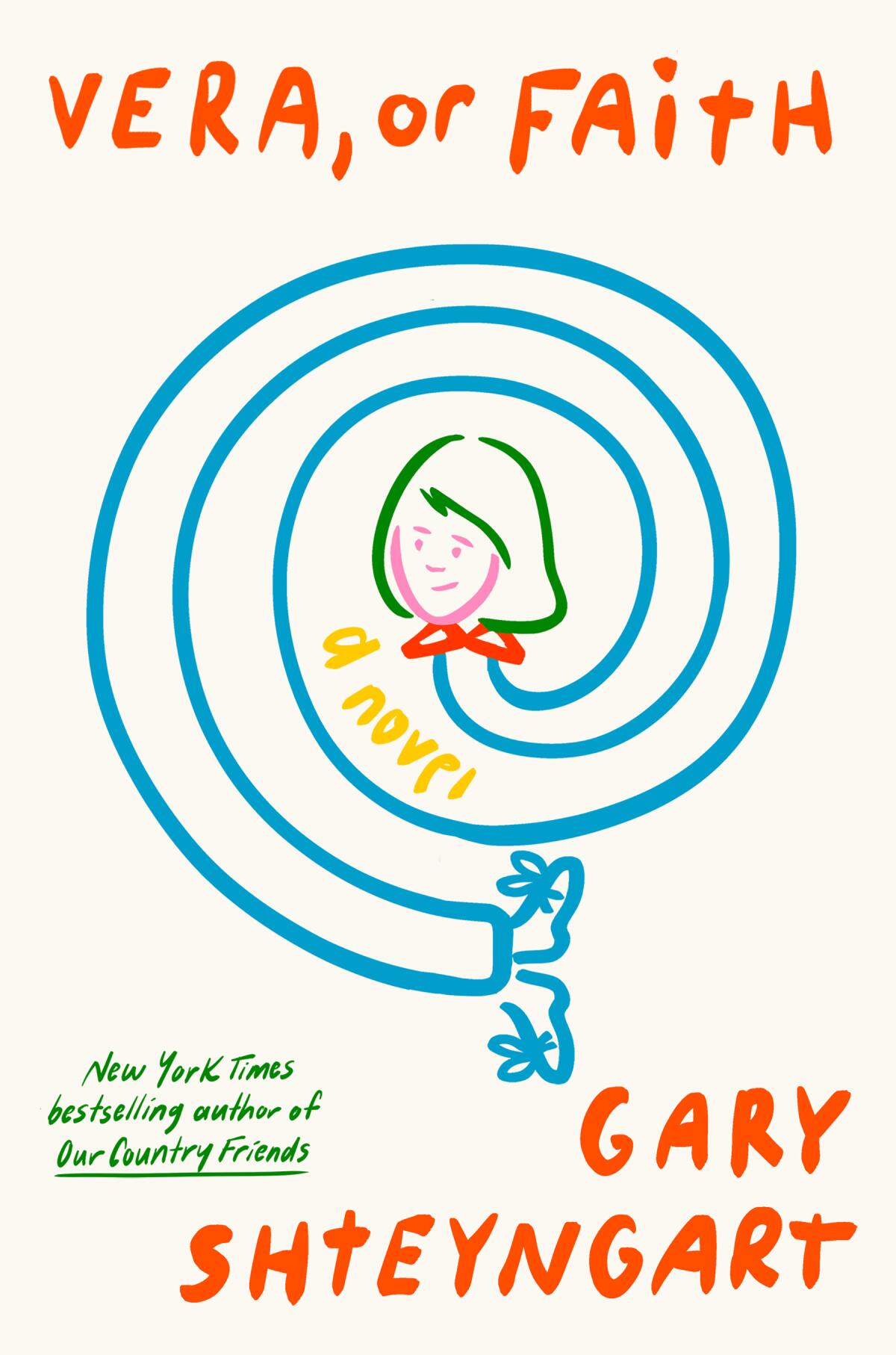

By Gary ShteyngartRandom Home: 256 pages, $28If you purchase books linked on our web site, The Instances could earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges help impartial bookstores.

Vera, the heroine of Gary Shteyngart’s sixth novel, “Vera, or Faith,” is a whip-smart 10-year-old Manhattanite, however she’s not fairly sensible sufficient to determine her mother and father’ intentions. Why is dad so involved about “status”? Why does her stepmom name some meals “WASP lunches”? How come each time they go to any individual’s home she’s assigned to see if they’ve a replica of “The Power Broker” on their cabinets? She’s all however doomed to be bourgeois and neurotic, as if a juvenile courtroom has sentenced her to dwell in a New Yorker cartoon.

Since his 2002 debut, “The Russian Debutante’s Handbook,” Shteyngart has proved adept at discovering humor within the intersection of immigrant life, wealth and relationships, and “Vera” largely sticks to that blend. However the cynicism that has all the time thrummed beneath his high-concept comedies — the dehumanizing algorithms, the rapacious finance system — is extra distinguished on this slim, potent novel. Vera is witnessing each the sluggish erosion of her mother and father’ marriage together with the fast decline of democracy in near-future America. Her precocity provides the novel its wit, however Shteyngart can be alert to the truth that a toddler, nevertheless brilliant, is essentially helpless.

To not point out determined for her mother and father’ affection, which is briefly provide for Vera. Her father, the editor of a liberal mental journal, appears always distracted by his efforts to courtroom a billionaire to buy it, whereas her stepmom is extra centered on her son’s ADHD and the household’s quickly dwindling checking account. Issues are not any higher outdoors on this planet, the place a constitutional conference appears able to move an modification awarding five-thirds voting rights for “exceptional Americans.” (Learn: white folks.) Vera, the daughter of a Russian father and Korean mom, could also be banished to second-class citizenry.

Even worse, her faculty has assigned her to take the facet of the “five-thirders” in an upcoming classroom debate. So it’s turn out to be pressing for her to grasp the world simply because it’s turn out to be inexplicable. Shteyngart is stellar at exhibiting simply how alienated she’s turn out to be: “She knew kids were supposed to have more posters on their walls to show off their inner life, but she liked her inner life to stay inside her.” And he or she appears to be dealing with the disaster with extra maturity than her father, who’s drunk and clumsy of their residence: “If anyone needed to see Mrs. S., the school counselor with the master’s in social work degree, it was Daddy.”

It’s a problem to jot down from the attitude of a kid with out being arch or cutesy — tales about youngsters studying about the actual world can degrade to plainspoken YA or low-cost melodrama. Shteyngart is striving for one thing extra supple, utilizing Vera’s viewpoint to make clear how adults turn out to be victims of their very own emotional shutoffs, the best way they use language to without delay seem sensible whereas protecting up their emotions. “Our country’s a supermarket where some people just get to carry out whatever they want. You and I sadly are not those people,” Dad tells her, forcing her to unpack a metaphor stuffed filled with ideology, economics, self-loathing and extra.

Each chapter within the guide begins with the phrase “She had to,” explaining Vera’s numerous missions amid this dysfunction: “hold the family together,” “fall asleep,” “be cool,” “win the debate.” Children like her need to be action-oriented; they don’t have the privilege of adults’ deflections. Small marvel, then, that her most dependable companion is an AI-powered chessboard, which provides direct solutions to her most urgent questions. (One in every of Shteyngart’s most potent working jokes is that adults aren’t extra intelligent than computer systems they command.) As soon as she falls right into a mission to find the reality about her beginning mom, she turns into extra alert to the world’s brutal simplicity: “The world was a razor cut … It would cut and cut and cut.”

Shteyngart’s grown-up youngsters’ story has two apparent inspirations: One, because the title suggests, is Vladimir Nabokov’s 1969 novel “Ada, or Ardor,” the opposite Henry James’ 1897 novel “What Maisie Knew.” Each are involved with childhood traumas, and if Shteyngart isn’t explicitly borrowing their plots he borrows a few of their gravitas, the sense that preteendom is a crucible for experiencing life’s numerous crises.

In its last chapters, the novel takes a flip that’s designed to talk to our present second, spotlighting the best way that Trump-era nativist insurance policies have introduced pointless hurt to Individuals. A rustic can abandon its rules, he means to say, simply as a father or mother can abandon a toddler. But when “Vera” suggests a selected imaginative and prescient of our specific dystopian second, it additionally suggests a extra enduring predicament for youngsters, who dwell with the results of others’ choices however don’t get a vote in them.

“There were a lot of ‘statuses’ in the world and each year she was becoming aware of more of them,” Vera observes. Kids must be taught them sooner now.

Athitakis is a author in Phoenix and writer of “The New Midwest.”